Kim Stanley Robinson on “The Barbarian” by Joanna Russ

Lisa Yaszek’s choice of “The Barbarian” to represent Joanna Russ in The Future Is Female! is a really good one. In many ways this story is a microcosm of all Russ’s fiction.

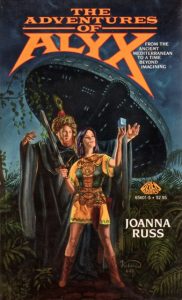

In his introduction to Alyx (1976), which collects all five Alyx stories in one book, Samuel R. Delany writes, “the critical temptation with a series is to try to read successive installments as if they were chapters in some particularly loosely-constructed novel,” but, he points out, “rather than successive chapters, they are really successive approximations of some ideal-but-never-to-be-achieved-or-else-overshot structuring of themes, settings, characters,” such that they are perhaps even “re-writes of the same story.” This is a good way to view “The Barbarian” not just within the Alyx sequence, but also across the whole span of Russ’s work, because all her fiction focuses repeatedly on just a few elements: mainly, what women should do in this moment of the patriarchy; secondly, what men should do.

Yes, Russ is a feminist. Yes, Russ is “angry.” But these words are much too reductive. They’ve become what people say about Russ, and this obscures our reading of her, or even keeps her from being read at all. People can think they don’t need to read her work, it being so one-dimensional; and from that position of knowledge-in-advance, which is to say ignorance, maybe it is. But not when you read it.

“The Barbarian” gives us Russ in full. In its brief span you see Russ is angry—or at least Alyx is angry. But the story is at the same time funny, smart, sensuous, suspenseful, beguiling. As for its anger, one thing the story wants to do is persuade you that you too would be angry if you were Alyx confronted by the fat man. When it was first published, the story’s readers were mostly men, or so they say, and surely almost all those men were persuaded, by way of fiction’s casting-of-the-self-into-the-other, to Alyx’s side. Consciousness-raising: this was what Russ was always doing. Of course fiction always does it. But Russ was very good at it, and this is partly, or maybe almost entirely, because she is such a pleasure to read.

For example, revisit with me this short passage from the story:

“If you can turn the city into gold,” said Alyx just as softly, “can you turn gold into a city?”

“Anyone can do that,” he said, laughing; “come along,” so they rose and made their way into the cold outside air—it was a clear night in early spring—and at a corner of the street where the moon shone down on the walls and the pits on the road, they stopped.

“Watch,” said he.

This could have been just getting the characters from A to B, but look at that syntax. I have to say, it’s a miracle this sentence got through so many reprintings without being mangled by some copy-editor or other, because the punctuation is unusual. Russ knows that, of course. She’s playing a game against standardized punctuation, but not arbitrarily; she’s using punctuation to create flow. She writes rhythmically, and the fine quality of her prose comes from a kind of a musical as well as a cognitive pleasure. Her writing resembles Virginia Woolf’s in the way it freely uses punctuation to create a flow state.

This virtuoso prose style is the main joy of reading Russ. Her sentences are incisive, dexterous, cheerful. While there is often anger in her content, in her form we are always hearing music. And even when you do focus on the content, it’s not always angry; she is often funny, and funny in different ways: ironic, sarcastic, genial, witty, hilarious. Always when reading her one feels that an extremely intelligent and observant person is directing one’s gaze to the most interesting thing at hand, with an invitation to enjoy it together.

“The Barbarian” is steeped in this amiability. It’s perhaps an unexpected quality in Russ, but actually very common in her work. When in The Female Man Janet walks up to an arrogant condescending youth and smacks him, it’s funny, even if you are much like that young man, as I was when I first read the scene. It’s unusual to have a slap to the face be not insulting but stimulating, in effect a kind of wake-up call in which the reader has been abruptly invited to take a larger perspective than he had before. Thus for me, and I suspect many others, reading Russ was a vital part of my education, because her fiction was delightful even when teaching quite alarming things. That delight fed understanding, and to understand is to change.

So “The Barbarian” is an early great entry in one of the most brilliant careers in American fiction. Russ should be as famous as Le Guin, yes, but also as famous as her teacher Nabokov. Over the long haul, I think she will be. Fashions in literature come and go, canons get established and then fall apart, but through it all books like hers endure, because readers love them and pass them along. Like Melville or Zora Neale Hurston, she will rise to the top. So I say: read Russ, or re-read her. She’s fun.

P.S. Larry Bigman informs me there is a sixth Alyx story that was left out of the collection, “The Game of Vlet,” which can be found in The Zanzibar Cat.

(Gage Skidmore/Wikimedia Commons)

Kim Stanley Robinson, the author of nineteen novels, has won multiple Hugo and Nebula Awards and the World Fantasy Award. Perhaps most widely known for his Mars trilogy, he has recently published New York 2140 (2017) and Red Moon (2018).