Sandra M. Gilbert on Joanna Russ and “The Barbarian”

I first met Joanna Russ when we were sixteen-year-old freshwomen at Cornell University, in 1953. Both of us thought well of ourselves: she had been a Westinghouse Science Prize winner in her senior year of high school, and I had graduated from New York’s prestigious Hunter College High School, where I had won a few poetry prizes. But we were also, as I vividly recall, nervous and homesick, stuck far off campus in the blocky, unpleasant dorm known as Clara Dickson Hall, to which most first-year women were routinely consigned.

How did we meet? I don’t even remember. Joanna wasn’t on my “corridor” (one’s corridor was one’s home place, complete with an alarmingly well-groomed upperclass counselor), yet I think she might even have lived on the same floor as me. In any case, we were both passionately literary and had signed on to the staff of the newly formed Cornell Writer.

And of course we were both confronting the usual “freshman rush.” On a campus where the “ratio”—a phenomenon often discussed in lowered voices, as if it were either some sort of embarrassment or some sort of magic—was five men to one woman, the fervor of men who wanted to scope out the women in the new class was a big deal, preceding and prophesying the later sorority/fraternity “rushes.”

There was one phone on every corridor, and it rang constantly, with male voices at the other end begging to speak to this one or that one, Meggy or Peggy or Sally, up and down the hall.

As a freshperson, Joanna was both spectacular and gloomy. She was nearly six feet tall, slender, slightly stooped, with dark hair and a long, lovely, sorrowful face that might have belonged to Virginia Woolf or George Eliot. No, not just lovely, but beautiful, with large woeful blue eyes.

I think I was “rushed” more than Joanna was, which was a source of sorrow to her and anxiety to me, to the extent that I was able to expend any energy on anxieties about others.

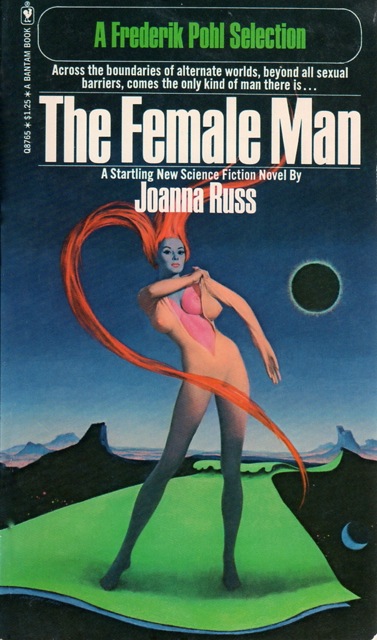

One afternoon I was forced to expend some energy. I came back from a class to find Joanna extended at full length on my bed with a box of kleenex beside her, weeping “copiously,” as some characters do in The Female Man. What had transpired? Some young man had abandoned her, insulted her, deceived her? I truly don’t remember, but I do recall trying to figure it out, and, later, to “fix her up” (as the saying went) with someone else, so we could “double date.”

As it happens, Joanna inadvertently introduced me to the man who would, four years later, become my husband. Elliot was a graduate student in English who read with great admiration a brilliant Gothic tale, “Harry Longshanks,” that Joanna published in the Writer quite soon after her arrival in Ithaca. He wrote her a fan note, took her out to dinner, then one day she casually introduced me to him, etc. etc.

Actually, she got quite angry at me when I first went out with him. We were both competitive—about writing, about men, about who was going to say what first about what book.

But Joanna was fiercely angry about many things, as we know from her fiction and her nonfiction. So was I. We were both, separately but with many combative moments, part of the fabulously angry Second Wave of feminism.

The Female Man is one of the great proof-texts of that anger, superbly exploring the different ways it got—or could be—expressed. So are Picnic on Paradise and The Two of Them.

And so, collected in The Future Is Female!, is “The Barbarian,” in which Joanna’s scintillating heroine/lithe other-self, Alyx, is asked to murder a baby girl by a fat, wicked, time-traveling patriarchal wizard who looks and sounds a lot like Sidney Greenstreet in Casablanca or The Maltese Falcon. How that Bad Guy giggles and wheezes! Joanna implies, at least from my perspective, that he may actually be GOD. Certainly he is a God-figure, because he has somehow made, or taken charge of, a couple of miserable worlds. And therefore it is crucial to murder him, though he claims he is invulnerable.

Joanna has always written great murder scenes—in The Female Man (for Jael), in Picnic on Paradise (for Alyx), and even in The Two of Them (for Irene). Jael has steel teeth. Alyx has a handy dagger. Irene has a fancy gun, though she is ambivalent about shooting her longtime appropriately named partner Ernst Neumann (Earnest Newman).

In “The Barbarian” we readers are grateful that Alyx can do away with the Sidney Greenstreet wizard. He has threatened the glowingly passive husband our heroine has sworn to protect, in one of Joanna’s usual renversements of patriarchal heterosexuality. We’re relieved to see his back broken, his futuristic toys destroyed, and our protagonist back with her “man.”

By the time she wrote The Female Man Joanna had changed some of that. Certainly Janet from Whileaway has a wife, not a husband, just the way some women do nowadays (one of my daughters, for example), in a cultural transformation that prophetic writers like Joanna helped to bring about.

Sandra M. Gilbert, Distinguished Professor of English Emerita at the University of California, Davis, is the author (with Susan Gubar) of The Madwoman in the Attic (1979) and many other works of literary criticism. She has also published eight collections of poetry—most recently Aftermath (2011)—and has edited several anthologies. Her website is www.sandramgilbert.com.

Sandra M. Gilbert, Distinguished Professor of English Emerita at the University of California, Davis, is the author (with Susan Gubar) of The Madwoman in the Attic (1979) and many other works of literary criticism. She has also published eight collections of poetry—most recently Aftermath (2011)—and has edited several anthologies. Her website is www.sandramgilbert.com.