Introduction by Lisa Yaszek

IV. Contributions

So what drew women to SF? Leigh Brackett cherished the “sense of wonder” associated with speculative fiction, asking “where else can I voyage among the ‘great booming suns of outer space’… shoot the fiery nebulae, and make planetfall anywhere I want?” Margaret St. Clair valued SF for leading “human attention into areas of experience that might not have otherwise been explored.”

Still others turned to the future in order to confront social and political issues in the imperfect present. Indeed, for Judith Merril, SF seemed like “virtually the only vehicle of political dissent” available to artists during the Cold War, enabling expressions of protest that publishers or audiences might otherwise have rejected. Joanna Russ believed similarly that SF could “crystallize an awful lot of things [people are] already feeling,” and could be particularly useful to minority authors hoping to convey new perspectives on science and society to wider audiences.

As they staked claims for themselves in the American future, women SF authors made major contributions to their chosen genre. First and foremost, they made complex character development a priority in a genre that initially excelled in big ideas and impressive gadgetry rather than emotional depth. As Andre Norton put it, hard science and technology might well be crucial to making a story SF, but what really interested her was “why people do things and how they might react.”

Women revised one of the oldest and most central relationships in SF: that of humans and aliens. Over the course of the nineteenth and early twentieth century, authors drew on widespread assumptions about Darwinian competition between species to cast aliens as bug-eyed monsters whose horrifying appearance reflected their equally horrifying desire to steal scarce resources from humans. But as early as 1928, Clare Winger Harris’s “The Miracle of the Lily” challenged such representations with its depiction of a man who meets intelligent insects from Venus. Other authors in The Future Is Female! who elaborate on the startling notion that humans might cooperate rather than compete with those who differ from them include Zenna Henderson, Rosel George Brown, and Ursula K. Le Guin.

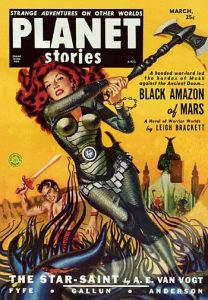

Women also challenged existing ideas about the natural hostility between species by telling tales from alien points of view. Leslie F. Stone pioneered this technique in her 1931 battle-of-the-sexes tale “The Conquest of Gola,” which invites readers to side with the female inhabitants of Venus as they ward off attack by their male Earthly neighbors. Subsequent authors including Margaret St. Clair, Carol Emshwiller, and Sonya Dorman refined this reversal of perspective to explore issues including sexism, racism, environmentalism, colonialism, and capitalism.

Not surprisingly, women revised science fictional representations of male-female relations as well. “Readers are tired of the yarn based on the super-hero and the ravishing babe,” Leigh Brackett warned would-be SF writers in 1944. For her, stereotypical Pulp Era romance narratives, full of stalwart space jocks with their requisite ray-guns saving hysterical damsels in distress from monstrous aliens, were simply “old stuff.” Fortunately, Brackett and many other contributors to this anthology felt that “you can get away with practically anything [in SF] as long as it’s well and subtly done.” Well before their explicitly feminist successors (or in a few cases their explicitly feminist future selves), many of the women included here were rethinking the gender roles that their male counterparts and the broader culture usually took as given—sometimes to an extent that might have been difficult to express without the imaginative freedom or allegorical cover of SF.

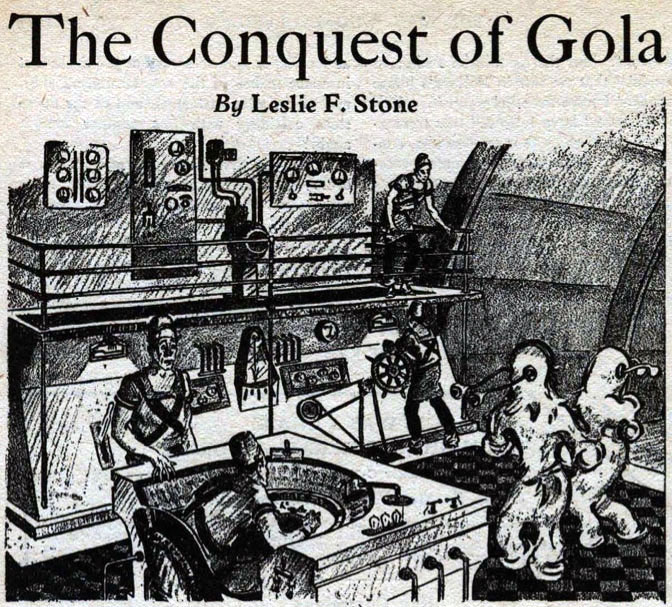

C. L. Moore introduced her “shero” Jirel of Joiry in “The Black God’s Kiss,” here featured on the cover of the October 1934 WEIRD TALES.

Instead of wish-fulfilling fantasies of masculine heroism, Doris Pitkin Buck, Kate Wilhelm, and James Tiptree, Jr. wrote stories in which male protagonists not only fail to save the women they love but turn out themselves to be responsible for the scientific and social situations that have endangered these women in the first place. Katherine MacLean, Andre Norton, and others cast women as experts who embrace alternate modes of science emphasizing intuition and empathy with the natural world. C. L. Moore, Leslie Perri, and Joanna Russ transform the damsels of SF cliché into “sheroes” who engage in quests and fight for truth and justice with almost superhuman strength, but who reject the stoicism, rugged individualism, and separation from nature that define the classic male hero. Still other stories by Judith Merril, Rosel George Brown, and Alice Eleanor Jones introduce readers to an entirely new character type: the housewife heroine whose relative happiness or unhappiness in the future becomes a barometer for evaluating the relative merits of our technocultural arrangements in the present.

Traversing interstellar voids, piloting vast spaceships, and exploring exotic planets as nimbly as male SF writers, the women of early SF also built intimate, down-to-earth worlds for speculation and reflection. The revelations of Wilmar H. Shiras’ mutant child story “In Hiding”—an influential text for the X-Men comics—unfold in an ordinary, present-day office and suburban home, spaces that seem as exciting in Shiras’ hands as any high-tech lab. Judith Merril’s midcentury classic “That Only a Mother” tackles the consequences of nuclear proliferation without special effects, in modest, near-future interiors. Zenna Henderson’s “Ararat” transforms a typical rural schoolhouse and its surroundings into a scene of alien and paranormal encounter. A first-grade teacher for all of her adult life, Henderson saw Kim Darby and William Shatner portray her characters in The People, made for TV in 1972.